The Rocket’s Red Glare

We’ve all heard the National Anthem hundreds of times, and those of us who live and work in Baltimore have all passed Fort McHenry hundreds of times. This low, black topsail schooner, with her unique profile, is often part of the scenery of Baltimore’s Inner Harbor. Unless we are mindful, these things, and the many other relics of our nation’s origins that stick up out of our physical and mental landscape here and there like dinosaur bones, will lose their meaning, buried under their own commonness. Each of these three things has a story all their own, that interlocks with the others, and also interlocks with the history of this city.

The Fort

Often, we have Scott Sheads, a retired Fort McHenry ranger and great friend of Pride, aboard for our day sails. I have never met anyone as deeply versed in the history of this city as Scott is. He tells us that Fort McHenry was the guardian of the city from 1812 to 1815, when the city was a collection of low buildings, largely centered in Fells Point, along a wide tidal river fringed with salt marsh. Eventually, by the time of shortly before the Civil War, the city grew around and past its former guardian, necessitating a new guardian, Fort Carroll, which was partially completed by a Colonel Robert E. Lee of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers before his life got complicated. By that time, of course, Fort McHenry was in no danger of being dismantled and its land repurposed. It was, and indeed remains, a national landmark. Because of:

The Battle

Most people know the basic story. The British sent a large fleet up the Chesapeake Bay to attack Baltimore. A young lawyer, Francis Scott Key, was a spectator aboard a British warship anchored in the harbor. After a night of bombardment, the sight of our national flag still flying from the Fort Mchenry the next morning led him to pen several stanzas of verse, which, when later set to music, became our National Anthem. The bombardment was unsuccessful. This, combined with a stalemate nearby at the land battle of North Point, made the situation untenable for the British, so they withdrew. But…what were they doing here? Why send a large fleet (and an army!) all the way up a narrow estuary to bombard a town that, by European standards, was pretty modest in size? The answer, in part, was:

The Ships

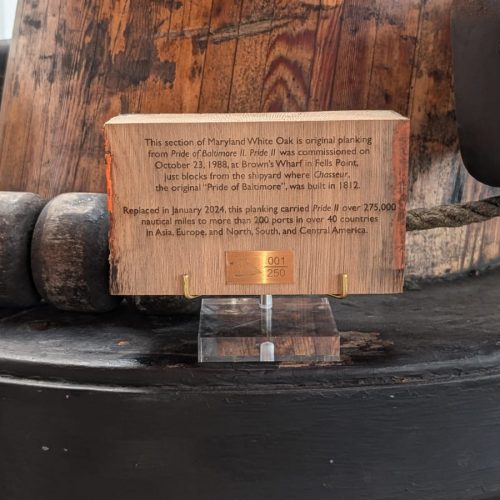

These ships, these low, sleek, sharply raked ships with their towering masts, once dotted this river by the dozens. Shipyards in Fells Point (which may be, visually, the most unchanged area of this city), like Thomas Kemp’s, kept building and building them, ever pushing the envelope of sharper hull, loftier spars, more sail, more speed. Speed, for them, was life. We sail Pride of Baltimore II fast because, well…we can. We sail her fast to evoke those historic vessels, products of the Chesapeake and of this city, that she represents. We sail her fast to compete, to show the modern world what a marvel these vessels were 200 years ago, and still are today. The fellows who sailed these vessels, Comet, Catch Me Who Can (I mean, what a name, right?) the famous Chasseur, and many others, did so for profit and to assist the war effort, but also for their freedom (not “freedom” as in political freedom, but freedom as in avoidance of prison), and often enough for their very lives. I’m motivated enough to drive Pride of Baltimore II hard just by the joy of competition, just to win a race. Imagine a race where it was death or prison if you lost.

My dad, a sailor and a lover of history like me, has this image of an 1812 privateer captain that he says I should try to emulate. I quote him roughly: “I always picture these guys as wearing a filthy peacoat, with a vest and tie or neckcloth underneath, and a bowler hat. They stalk the deck with a steely glare, as the ship flies along under a huge cloud of canvas, everything stretched to the breaking point. The crew takes an occasional fearful glance aloft, but all the captain says to them is “Drive her, boys. Drive her.”

A little silly, yes? It was meant to be. But it becomes less so when you look over the captain’s shoulder, over a couple of miles of white-capped sea, at the pursuing British frigate. Those men in their filthy peacoats and bowler hats, sailing out of this city, won those races often enough, for profit, as a war aim, and for their lives, that the British saw eradicating the shipyards that built their fast ships here in Baltimore as an important enough goal to sail a huge fleet here and try to blast their way into the city. And the image of those ships, that unique shape that struck fear into their prey and frustration into their pursuers, endured long enough for this city to build two of them more than a century and a half later.

All of this, by the way, clicked together as a tale to tell as I sat on Pride last night, and watched a red rocket burst over Fort McHenry.

Signed,

Captain Jordan Smith