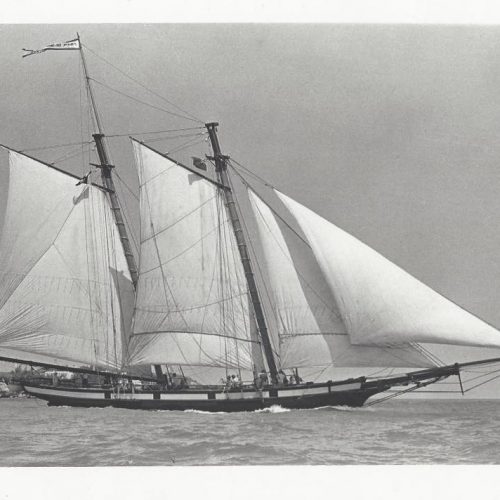

As Pride of Baltimore looks ahead to its next fifty years, we continue to tell our story. The history of the Baltimore Clipper and the Chesapeake is inseparable from the lives of the people who worked these waters before us. Among them were thousands of African American sailors whose presence, labor, and experience shaped maritime life in ways that are often overlooked. This rich history cannot be adequately conveyed in a single blog post and will be covered in future blogs. If you are interested in learning more about this subject, we recommend purchasing a copy of Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail by Jeffrey Bolster, which was used extensively to tell this story.

Through our collaboration with the Blacks of the Chesapeake Foundation, we are committed to highlighting the role of African American mariners who shaped the maritime world of the Chesapeake and the wider world. The video below was made possible through funding from the Chesapeake Crossroads Heritage Area.

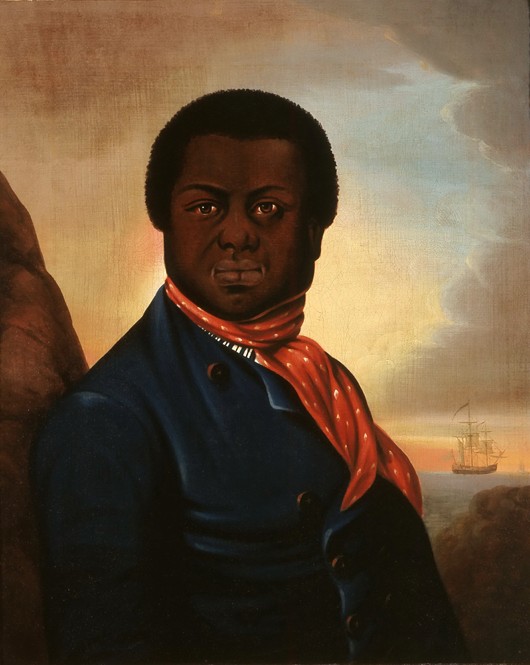

Black Jack: A historical term used in the Age of Sail refers to a Black sailor.

Catch up on past parts of our blog here.

Popular imagery of African Americans at sea has long been dominated by the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade. While that history is essential to acknowledge, it has also obscured a more complex association between African Americans and maritime work. As historian Jeffrey Bolster highlights in his book, Black Jacks, Black mariners were a highly visible and integral part of the Atlantic world. In the early nineteenth century, more than 100,000 Black men went to sea each year, filling roughly one-fifth of all sailors’ berths. As Bolster notes, Black jacks were a common sight on the docks.

Seafaring was ultimately an occupation of opportunity for both free and enslaved African Americans. Maritime wages offered access to income, mobility, and experience otherwise denied to most Black workers ashore. Those wages allowed some enslaved sailors to purchase freedom but also supported churches, benevolent societies, and other institutions through which Black Americans established an organized presence and a public voice. Bolster observes that “Black seamen found access to privileges, worldliness, and wealth denied to most enslaved people.”

The influence of Black sailors extended beyond the waterfront. Sailors authored the first six autobiographies by Black writers published in English before 1800. These works bridged oral Black culture with what had previously been an exclusively white literary world and marked the beginning of a sustained body of antislavery writing by Black authors. As Bolster notes, Black seafaring men were in the vanguard of defining a new Black ethnicity for African peoples dispersed by Atlantic slavery.

Life at sea, however, was neither easy nor free of danger. Black seamen navigated what Bolster describes as a “torturous channel” through the North Atlantic, “beset by the deeply felt oppression of race and slavery, by commercial capitalism’s sustained exploitation of maritime workers, and by the danger of the deep during an era of frail wooden ships.” Yet within these constraints, Black sailors continued to pursue autonomy and opportunity through maritime labor.

One of the most significant tools available to them was the Seamen’s Protection Certificate. These documents identified the bearer as an American citizen and, in the case of African Americans, affirmed their free status. Originally intended to prevent American sailors from being impressed into the British Navy during the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, protection certificates became invaluable to those seeking freedom. While some papers were forged, free Black sailors also loaned their certificates to others in need.

Frederick Douglass’s escape in 1838 is among the best-known examples. Enslaved in Maryland, Douglass had been hired out as a caulker on the Baltimore waterfront. Caulkers sealed the seams of wooden hulls, and through this skilled trade, Douglass became familiar with sailors, their speech, and their dress. He formed relationships within the maritime community, including a friendship with a free Black sailor named Benny.

Douglass borrowed Benny’s Seamen Protection Certificate and traveled north disguised as a sailor. At the time, protection papers relied solely on written descriptions and did not include photographs. Combined with the widespread presence of Black sailors in northern ports, this allowed Douglass to move with relatively little scrutiny. He reached New York and secured his freedom.

Although Douglass would later become one of the most influential abolitionists of the nineteenth century, he continued to work as a caulker when not traveling or speaking. Maritime labor remained a practical and familiar occupation even after his escape.

Any honest accounting of African Americans and the sea must reckon with its contradictions. The same ships that carried enslaved people across the Atlantic also served, at different moments and under different circumstances, as pathways to freedom. Maritime spaces were neither uniformly liberating nor wholly oppressive. They were complex, contingent, and shaped by who held power aboard and ashore.

For enslaved people seeking escape, ships offered mobility and anonymity that were difficult to replicate on land. For Black men who possessed maritime skills, especially experienced sailors, the sea could provide a degree of protection, liberation, and worldliness unavailable elsewhere. As Bolster documents, seamanship created opportunities that were practical as well as social, placing Black mariners within transatlantic networks of labor, information, and movement.

Following the American Revolution, a first generation of free Black Americans went to sea in unprecedented numbers. Few other workplaces admitted them so readily. During the Revolutionary War, Black men served aboard privateers and in the Continental Navy. The War of 1812 expanded this participation further, drawing an estimated 18,000 free Black sailors into American maritime service.

The decades following the War of 1812, however, marked a gradual decline in the number of Black sailors. This shift reflected several overlapping factors: the aging of veteran seamen, hardening racial attitudes, and economic changes that reshaped maritime labor and restricted access. While exceptions remained, the broad trend was toward exclusion rather than inclusion.

Still, the legacy of Black seafarers endures. Their labor sustained maritime economies, their wages supported Black institutions ashore, and their experiences helped shape early expressions of African American identity and resistance. To tell the story of the Chesapeake, the Baltimore Clipper, and the wider Atlantic world is to acknowledge both the violence embedded in maritime history and the ways Black sailors navigated that world in pursuit of opportunity, autonomy, and freedom.