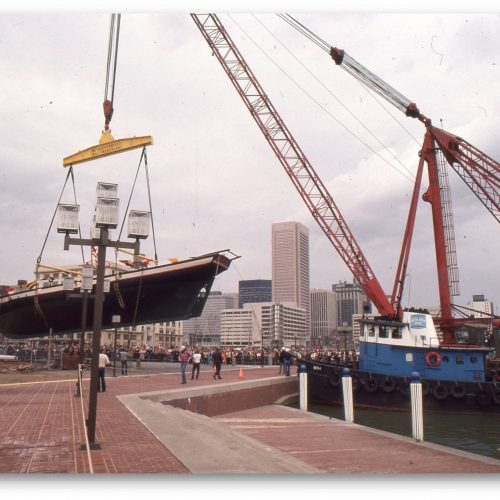

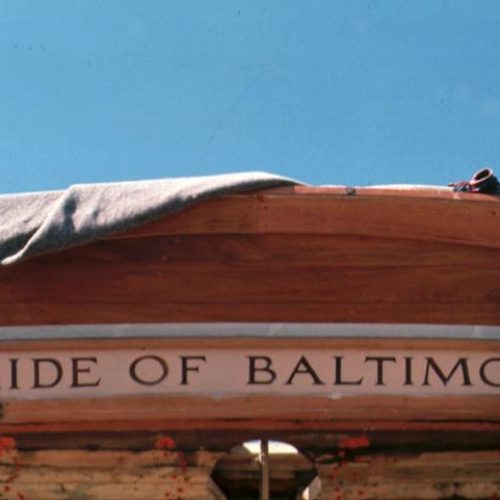

As we continue our weekly 50 Years of Pride series, we find ourselves at a rare convergence of history. In 2026–2027, milestones of remembrance, restoration, and national celebration align, creating a moment that is both reflective and forward-looking. The 40th anniversary of loss, the rededication of the Pride of Baltimore Memorial, and America’s upcoming 250th anniversary invite us to look not only at where Pride has been, but at the deeper history she was built to represent.

At her core, Pride of Baltimore II embodies the pinnacle of a very specific American maritime tradition: fast, weatherly vessels designed for the practice of privateering.

Catch up on past parts of our blog here.

Image: A hand-colored aquatint depicting Baltimore, Maryland, in 1752 as viewed from the harbor. The print also includes a list of 29 different landmarks that are visible in the image. The caption beneath the image reads: BALTIMORE IN 1752, From a Sketch then made by John Moale Esq. deceased, corrected by the late Daniel Bonley Esq. “from his certain recollection, and that of other aged persons, well acquainted with it, with whom he compared Notes.”

Baltimore in 1752

Creator: William Strickland, 1787-1854 Date 1817

Courtesy of The Maryland Center for History and Culture Resource ID 2368

Privateers were not pirates, though history, popular culture, and wartime propaganda have often blurred that distinction. Since the late nineteenth century, public imagination has been dominated by romantic pirate imagery: Blackbeard, Captain Kidd, Henry Morgan, buried treasure chests, and “pieces of eight.” Fictional figures like Long John Silver or Captain Jack Sparrow only reinforce the idea that anyone who captured ships for profit must have been a pirate.

The historical reality was far more complex. Privateers were privately owned vessels operating under government authorization, issued through letters of marque and reprisal, allowing them to capture enemy shipping during wartime. Their actions were legal, regulated, and strategically important.

Some well-known figures did cross the line. Sir Francis Drake began as a sanctioned privateer under Queen Elizabeth I, helping finance England’s defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, but later acted more independently and was viewed by Spain as a pirate. Henry Morgan and William Kidd followed similar paths. Perception also depended on who told the story. In 1778, British newspapers branded John Paul Jones a bloodthirsty pirate during his raids on the Irish coast, despite his legitimate commission. Likewise, the corsairs of Tripoli, Tunis, and Algiers were labeled “Barbary pirates” by Americans in the early nineteenth century, even though they operated with legal sanction from their own governments.

During the American Revolution, privateering in the United States took on a distinctly different character than earlier European practice. As Jerome R. Garitee explains in The Republic’s Private Navy, American privateering was reshaped by the circumstances of revolution. English capital was largely replaced by American and foreign investment. Licensing, supervision, and prize adjudication were handled by American authorities rather than imperial courts. Most importantly, the pursuit of profit was accompanied by an unprecedented sense of patriotic purpose. American privateers took risks against enemy warships, cooperated with one another at sea, shared intelligence, and worked in concert with the Continental Navy. Garitee argues that the United States depended on its privateers to a degree unmatched by contemporary European monarchies, making them a central pillar of American naval power.

This reliance was born of necessity. The young United States lacked a large standing navy, particularly in the early years of the war. In March 1776, Congress authorized the issuance of letters of marque and reprisal, though Rhode Island anticipated the move by issuing commissions as early as the summer of 1775. General George Washington relied heavily on licensed privateers to disrupt British supply lines, capture vital stores, and interfere with enemy communications. As Garitee notes, Washington himself even owned a share in a privateer.

Baltimore emerged as one of the most effective privateering ports in the colonies, though the vessel type later known as the Baltimore Clipper had not yet been named. In The Baltimore Clipper, Howard Irving Chapelle explains that when the Revolution began, the swift schooners that would later define Baltimore were often referred to simply as “Virginia-built.” These vessels, developed out of necessity, proved exceptionally fast and increasingly successful as the war progressed.

Chapelle emphasizes that the colonies could not wage a traditional naval war, yet still needed ships capable of procuring munitions and supplies while operating under blockade. Fast vessels became essential for both trade and privateering. As the war continued, larger and more heavily armed schooners became common, including vessels carrying ten, sixteen, and even twenty guns. Chappelle continues to share that “it not erroneous to state that fifty percent of the American vessels engaged in this business after 1778, were ‘Virginia-built’ type or model.”

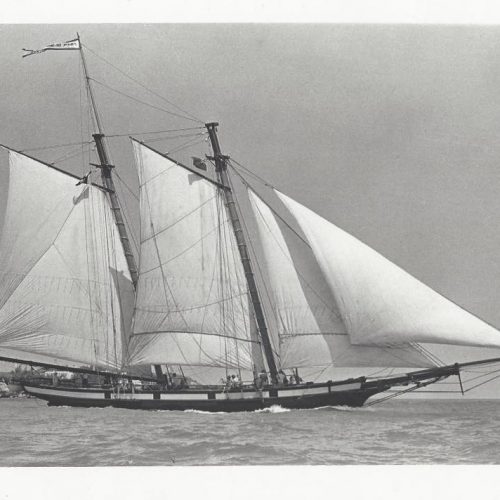

The scale of privateering expanded rapidly. Chapelle notes that the number of American privateers grew from approximately 142 vessels in 1776 to more than 320 by 1782. Schooners built for fast sailing proved remarkably effective despite the odds they faced. By the end of the Revolution, the vessel type that would later be recognized as the Baltimore Clipper was well known and widely admired. These schooners were large, heavily armed, and aggressively sparred. Their speed and success attracted international attention, and they appear frequently in English, French, and Dutch naval histories. Many details of their development have since faded, as Chapelle observes, leaving builders and designers largely anonymous, lost to time.

This is the lineage Pride of Baltimore II was designed to honor. She is not a replica of a single historical vessel, but a living expression of the qualities that made Baltimore privateers so effective: speed, power, weatherliness, and purpose. As America approaches its 250th anniversary, Pride offers more than a sailing experience or a striking silhouette under sail. She is a tangible link to the maritime strategy, commerce, and innovation that helped secure American independence.

Privateering helped win a revolution.

Baltimore helped shape the vessel that made it possible.

Pride of Baltimore II keeps that story alive.