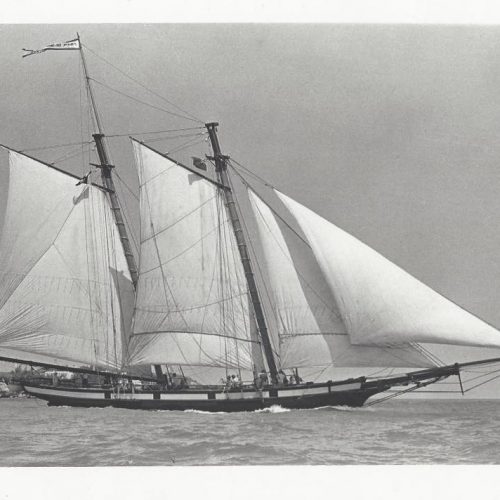

This week gives us a wonderful excuse to honor one of Baltimore’s most legendary ships. As we mark the December 12, 1812 launch of Chasseur, it’s the perfect moment to revisit her remarkable legacy. If Hollywood ever needs a ready-made maritime blockbuster, they could start with Captain Thomas Boyle and the schooner Chasseur. Daring Atlantic crossings, bold proclamations in the heart of London, and battles against larger ships, her story reads like pure adventure. As we approach the anniversary this Friday, we’ll share just a few highlights from her globe-spanning saga and we think they’ll leave you wanting more.

Thomas Kemp & the Shipyard that Built Chasseur

According to Thomas Gillmer in his book, Pride of Baltimore: The Story of the Baltimore Clippers, the records on Kemp’s earliest years in Baltimore are incomplete, but by July 1805, he had already purchased the property that became his own shipyard. Maps and contemporary directories from 1800–1820 place his shipyard between Philpot Street and the Ann Street wharf, in the heart of present-day Fells Point. There, he began turning out pilot-boat-style schooners; these powerful and fast vessels were well suited for trade, blockade-running, and eventually privateering. This was years before the 1812 declaration of war, but the design proved ideal for escaping threatening situations and outrunning pursuers.

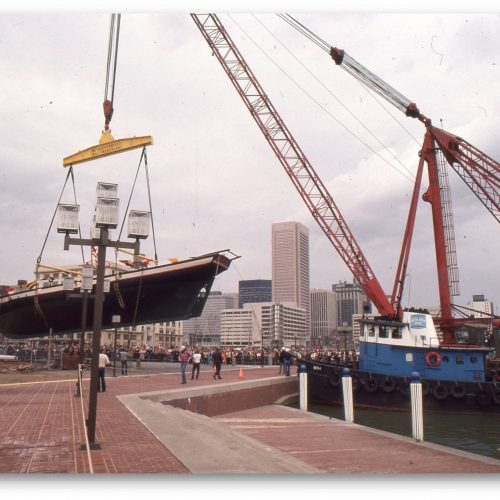

Launch of Chasseur, December 12, 1812

Chasseur was launched on Friday, December 12, 1812. The launch was announced in the December 17 issue of the Baltimore Federal Gazette. That same notice reported that she would soon sail for France under the command of Captain Pearl Durkee, with freight for the voyage being accepted.

Though celebrated today as a privateer, Chasseur was originally intended to be a swift commercial carrier. Her owner documented her with a letter of marque, meaning she was licensed to carry cargo and defend herself, but not primarily outfitted for offensive prize-taking. (A true privateer was commissioned solely to capture enemy vessels for profit.)

A Difficult Start: Failed Voyages & a Mutiny

Her first voyage began in February 1813. It was to be a trading mission to France; she departed Baltimore and met the British Blockade in the Chesapeake Bay. After some dawdling, she returned to Baltimore and remained idle through the summer. A second attempt to run the British Blockade in September 1813 also failed. Gillmer attributes the failures to the captain’s excessive timidity. The second incident escalated dramatically into a mutiny; the court ultimately dismissed the case on a technicality.

During the trial, Chasseur was refitted and recommissioned as a privateer. Her new captain was William Wade, who had previously served under Thomas Boyle aboard Comet. Wade sailed Chasseur out of the Virginia Capes on December 26, 1813, slipping past the British blockade under cover of a snowstorm. Though often overshadowed by Boyle’s later exploits, Wade carried Chasseur into European waters and captured six prizes off the coast of Portugal.

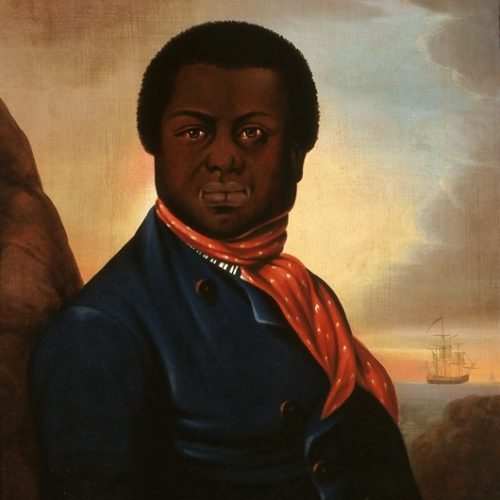

The Boyle Era & Chasseur’s Fame

Chasseur was eventually sold and brought north, and Thomas Boyle took command in New York in mid-1814. Under Boyle, she began her storied privateering cruise to the British Isles. It was on this voyage that Boyle proclaimed one of the “most audacious and least remembered messages in the history of naval warfare. Boyle, with one Baltimore clipper schooner and less than 100 men, declared the coasts of Great Britain and Ireland in a state of blockade. ” — Fred W. Hopkins, Jr, Tom Boyle: Master Privateer

This proclamation was passed along by a captured vessel and delivered to Lloyd’s Coffee House in London, the center of Britain’s insurance business. Boyle’s claim that he had force sufficient to blockade all of Great Britain was a jab at the British “paper blockade” of the US Coast. But the threat had an impact; within days, insurance rates soared, and Royal Navy ships were diverted to hunt down Chasseur.

After taking 10 prizes and seizing $100,000 in cargo, Boyle turned for home. The original ship’s crew was reduced from 150 to 60 due to the assignment of prize crews. Upon arriving in New York, the Niles Register reported Chasseur brought in 43 prisoners in addition to having paroled 150 more during the three-month cruise. The register further estimated that had Boyle destroyed every ship he stopped, the loss for the British would have been over $1.5 million dollars.

‘Pride of Baltimore’

On March 15, 1815, while on a privateer cruise to the Caribbean, Boyle received the news that the Treaty of Ghent had been ratified, and the war was over. He turned for the Chesapeake and arrived back in Baltimore on March 25, 1815. Niles Register would later report:

“Perhaps the most beautiful vessel that ever floated on the ocean … she sat as light and buoyant on the water as a graceful swan, and it required but very little imagination to feel that she was about to leave her watery element and fly into the clear, blue sky. She is truly the pride of Baltimore.” — Niles’ Weekly Register, April 15, 1815,

In the book Men of Marque, authors Cranwell and Crane describe Chasseur as “one of the finest” vessels to come out of Baltimore.

Post War Duties

After her last voyage with Boyle, Chasseur was auctioned off to new owners who fitted her out as a merchant vessel. The owners hired former privateer captain Hugh Davey to sail her to Canton, China, to secure a cargo of silk, tea and dry goods. On her return voyage, Davey and Chasseur set a speed record of 95 days from Canton to the Virginia Capes (a trip that might have been even faster had they not stopped to help a longboat filled with women and children from a wrecked Dutch East Indiaman). This record stood for 16 years until it was broken by Atlantic in 1832.

Chasseur remained a merchant vessel until the summer of 1816. While in Havana, she was purchased and renamed Cassidor and entered into service in the Spanish Navy to combat privateers. It is reported that she was bested in an engagement with the Mexican privateer Hotspur in July of 1816.

Recent research done by retired park ranger and historian Scott Sheads turned up a mention in the New Bedford Mercury in January of 1822. The short article notes that “Several vessels were wrecked in the Old Bahama Channel (just off the north shore of Cuba) on 1st Dec. last, among them were the Spanish man-of-war Almirante, (formerly the Chasseur, of Baltimore).”

Now, whether this was the Chasseur or another vessel with the same name is still unknown. Either way, over the years, our Chasseur slipped quietly from the historical record; her final fate is largely unknown.

Bibliography:

Chapelle, Howard I. The Baltimore Clipper. Bonanza Books, New York, NY 1930

Cranwell, John Philips, & William Bowers Crane. Men of Marque: The Story of Privateers of America. New York: W.W. Norton, 1940.

Fred W, Hopkins, G. Tom Boyle: Master Privateer. Mattituck, NY Ameron House, 1976

Gillmer, Thomas C. Pride of Baltimore: The Story of the Baltimore Clippers. International Marine, Camden, ME 1992

Niles’ Weekly Register. Baltimore. Vol. 8 (March–September 1815).