Pictured Left: Nancy Aldrich at Pride II‘s helm on a sail in Baltimore Harbor, 2015.

Pictured Right: Nancy’s father, John Aldrich, at Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum dock, St. Michaels, 2001.

This story was submitted by Nancy Aldrich, whose third great grandfather, Thomas Kemp, built Chasseur—Baltimore’s most famous privateer. Nancy is writing a genealogy/biography of Thomas Kemp based on his own records and papers. Read the full story below.

My story is not so much about sailing on Pride (although I have done that in Baltimore Harbor as a guest), but of loving Pride for so, so long…

My third great grandfather Thomas Kemp built the Chasseur. Kemp’s vessel was nicknamed the “Pride of Baltimore” by the people of Baltimore, after she humbled the British in battle (War of 1812). I grew up listening to family stories of the successful exploits of this beautiful privateer ship. My favorite quote has always been from the weekly Baltimore Niles Register, in 1815:

“She [the Chasseur] is, perhaps, the most beautiful vessel that ever floated in the ocean, those who have not seen our schooners have but little idea of her appearance. As you look at her you may easily figure to yourself the idea that she is about to rise out of the water and fly in the air, seeming to set so lightly upon it!”

Kemp launched his pilot schooner Chasseur on 12 December 1812, according to the Baltimore Federal Gazette. He signed the carpenter certificate in January 1813. Thomas Kemp wrote in his journal: “finished privateer built with a round tuck and no head” (Jan. 8, 1813).* It was built for William Hollins and Michael McBlair (it quickly changed hands), although Kemp wisely kept a share in the ownership.

Growing up, I consumed any article I could find about Chasseur, plus reading the reprints of her ship logs in the Maryland Historical Magazine published in 1906 and 1939. At the Maryland Center for History and Culture, I have held the logbooks to several of Kemp’s ships in my hands, and felt a warm connection to centuries past.

Maritime author Geoffrey Footner noted that a set of line drawings for Chasseur “was at one time in France’s Musee de la Marine at Toulon, but was stolen in the 20th Century” (A Bungled Affair, p. 118). How I would love to see that thief arrested and see those drawings returned. Maybe someday they will surface?

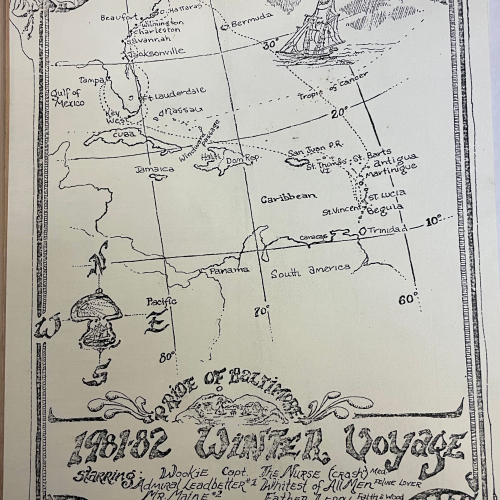

Baltimore’s decision to build a replica ship was exciting to my entire family (my mother grew up at the Wades Point house that Thomas Kemp built in Talbot County in 1821). We closely followed the news of the building of the Pride of Baltimore in 1977. We visited Pride several times, plus loved to see her out sailing on the Chesapeake Bay. (My Dad had a painting commissioned of her rounding Sharp’s Island lighthouse that was made from a photograph he took.)

The sinking of the first Pride in 1986 was such a shock and a loss. I heard the 10 bells go off on the UPI machine in my office and ran over to read the news. Everyone else in my office gathered around to see what had happened, but then quickly drifted away when they heard it was “only” a replica ship sinking. I could have cried! I felt so crushed, and so alone in my sorrow. I still have that UPI printout, although the purple ink has long since faded to almost oblivion.

My family supported the building of the second Pride, and were thrilled when she was launched in 1988. Four generations of my family have climbed on board Pride II to have a look at that beautiful sailing ship. (I actually steered her briefly one lovely evening in Baltimore Harbor–thank you generous captain!)

I am currently writing a genealogy/biography of Thomas Kemp based on his own records and papers—which lay in the same desk in the same house at Wades Point where my mother grew up. In working on the book, I have found much erroneous information about Kemp. (For one, he was never a Quaker. Also, Frederick Douglass never worked for him. Douglass was a slave in 1835 (long after Kemp had died in 1824) in that Fells Point shipyard, which Kemp turned over to George Gardner.)

This family history gives me a strong connection to Pride II and I love to hear news about her. She is such a great emblem of the glorious shipbuilding days of the Chesapeake Bay. May she sail forever!

Nancy Aldrich

*Round tuck- type of stern, as opposed to a square tuck. It is a stern that is formed by the turning up of the after planking to meet and be fastened to a heavy cross timber called the transom beam No Head- Lack of a figurehead on the stem.

####